CLIs Serving UIs

Countless times I’ve found myself shipping CLI tooling amongst teams or co-workers. The challenge of onboarding users to a new CLI is that there’s a whole new set of commands, subcommands, flags, and arguments for the user to work with. While my daily workflows are essentially built on CLIs, there’s no doubting that a UI can ease the on-ramp and usability of your tooling.

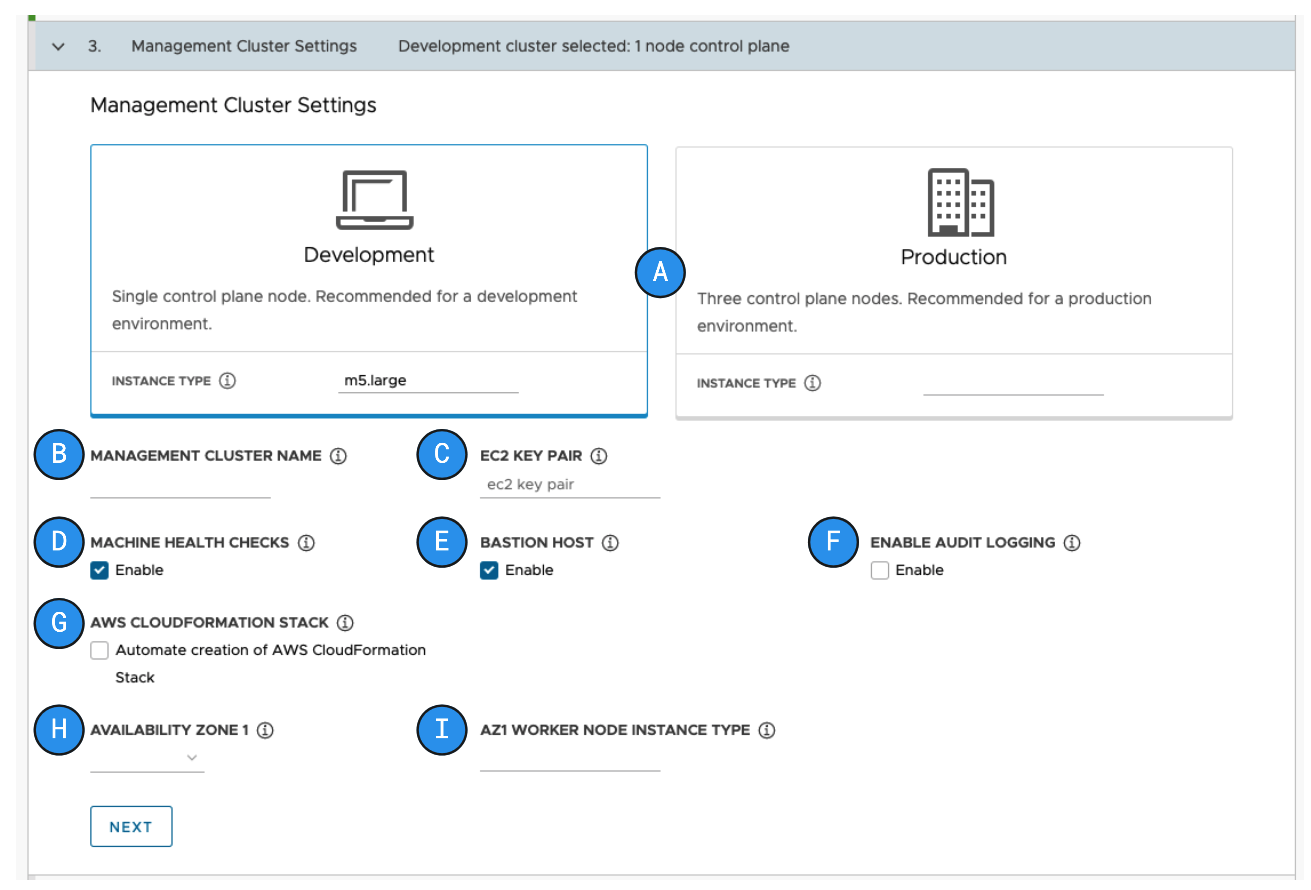

When I was working on Tanzu Community Edition at VMware, I saw first hand how

successful a UI could be. The tanzu CLI was responsible for creating

Kubernetes clusters. Rather than having users create multiple YAML files and

learn the implications of various flags, they could launch a UI that took them

through the options.

This created an excellent on-ramp for a complex tool, while still enabling power users to do everything through configuration and flags. As you can tell from the screenshot above, that UI was quite fancy and built using node packages, Javascript frameworks, etc. So for most of us, we’ll need something with significantly less overhead.

I believe we can accomplish this using modern languages like Go or Rust. These languages provide simple means of spinning up web servers along with templating libraries where we can render HTML based on our underlying data structures.

Today I’m going to look at adding a front-end to proctor, a CLI responsible

for surfacing details around processes and their relationships. The end state

will be a frontend that can be triggered from the CLI and look something like

this:

Architecture

When I create non-trivial CLI tooling. There’s an pattern I tend to repeat over

time. This pattern surfaces in how packages (or libraries) are built. In the

case of proctor it looks like:

Each piece of core functionality ends up in its own *lib package. This ensure

the library can be imported into other projects and used without interaction of

the CLI and not taking on transitive

dependencies

of the CLI. Additionally, by treating the CLI, and eventually UI, as an importer

of the underlying libraries, it forces me to consider what I should be exposing

at the package-level and how my API should be designed.

Once the libraries are in place, the CLI code and UI code become nothing more than defining user interaction for their respective models. Lastly, there are a set of packages such as configuration or logging that all packages are allowed to import, thus these standalone to ensure there aren’t any circular dependency problems.

For today’s purposes, all of the above pre-exists minus the UI block above.

We’re going to dig into what it’ll look like to hook into the plib (process)

library along with call the UI from the CLI itself. To get an idea for some

functionality we’ll build a UI around, one thing proctor can do is surface known

process, important details about them and their hierarchy. Here are 3 examples

that show the flow a user might go through.

Listing processes:

# proctor ps ls

+--------+-------------------------------------+-----------------------------------------------------------+------------------------------------------------------------------+

| PID | NAME | LOCATION | SHA |

+--------+-------------------------------------+-----------------------------------------------------------+------------------------------------------------------------------+

| 1422 | wrapper-2.0 | /usr/lib/xfce4/panel/wrapper-2.0 | 37422e15cc11ed476eb5019d73e8bf1a00d2c8f63b027b639bfacf864a5fb88a |

| 43233 | chrome_crashpad_handler | /usr/lib/chromium/chrome_crashpad_handler | c8a36670bfd7505e0a58866f9cd8a84a0ade2fca983491e0fb70092646d620af |

| 67956 | bash | /usr/bin/bash | 864925e8e16b3c2bc999c77e4959f20b4834e48f49b966e550e00e13dc01f9b7 |

| 1363 | xfce4-panel | /usr/bin/xfce4-panel | 069c098a8e5d253b60ddbb9784574b51ff397273f146a21f11fe7b8cfcde3e65 |

| 3259 | bash | /usr/bin/bash | 864925e8e16b3c2bc999c77e4959f20b4834e48f49b966e550e00e13dc01f9b7 |

| 58079 | chromium | /usr/lib/chromium/chromium | 9e49ab8e46367c7229f07a7227753360e39932f276c523a0ddff58fcbbbb0080 |

| 1334 | xfwm4 | /usr/bin/xfwm4 | 024da2825e5d28dcdf73987c36bd28dba183e012f24af61b803e224e6cab7a69 |

+--------+-------------------------------------+-----------------------------------------------------------+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Getting details around a process:

# proctor ps get --id 1334 -o json | jq . > ~/clip

{

"ID": 1334,

"BinarySHA": "024da2825e5d28dcdf73987c36bd28dba183e012f24af61b803e224e6cab7a69",

"CommandName": "xfwm4",

"CommandPath": "/usr/bin/xfwm4",

"FlagsAndArgs": "",

"ParentProcess": 1273,

"IsKernel": false,

"HasPermission": true,

"Type": "linux",

"OSSpecific": {

"ID": 1334,

"FileName": "(xfwm4)",

"State": "S",

"ParentID": 1273,

"ProcessGroup": 1273,

"SessionID": 1273,

"TTY": 0,

"TTYProcessGroup": -1,

"TaskFlags": "4194304",

"MinorFaultQuantity": 19523,

"MinorFaultWithChildQuantity": 0,

"MajorFaultQuantity": 60,

"MajorFaultWithChildQuantity": 0,

"UserModeTime": 8030,

"KernalTime": 5154,

"UserModeTimeWithChild": 0,

"KernalTimeWithChild": 0,

"Priority": 20,

"Nice": 0,

"ThreadQuantity": 17,

"ItRealValue": 0,

"StartTime": 1398,

"VirtualMemSize": 1937858560,

"ResidentSetMemSize": 27973,

"RSSByteLimit": 9223372036854776000,

"StartCode": "0x55cfe3fca000",

"EndCode": "0x55cfe400750d",

"StartStack": "0x7fff639ef3c0",

"ExtendedStackPointerAddress": 0,

"ExtendedInstructionPointer": 0,

"SignalPendingQuantity": 0,

"SignalsBlockedQuantity": 0,

"SignalsIgnoredQuantity": 4096,

"SiganlsCaughtQuantity": 16899,

"PlaceHolder1": 0,

"PlaceHolder2": 0,

"PlaceHolder3": 0,

"ExitSignal": 17,

"CPU": 3,

"RealtimePriority": 0,

"SchedulingPolicy": 0,

"TimeSpentOnBlockIO": 0,

"GuestTime": 0,

"GuestTimeWithChild": 0,

"StartDataAddress": "0x55cfe401a330",

"EndDataAddress": "0x55cfe401d140",

"HeapExpansionAddress": "0x55cfe5803000",

"StartCMDAddress": "0x7fff639efb5e",

"EndCMDAddress": "0x7fff639efba8",

"StartEnvAddress": "0x7fff639efba8",

"EndEnvAddress": "0x7fff639effe9",

"ExitCode": 0

}

}

Retrieve parent/child process relationships:

# proctor ps tree

proctor ps tree 1334

+------+---------------+--------------------------+------------------------------------------------------------------+

| PID | NAME | LOCATION | SHA |

+------+---------------+--------------------------+------------------------------------------------------------------+

| 1334 | xfwm4 | /usr/bin/xfwm4 | 024da2825e5d28dcdf73987c36bd28dba183e012f24af61b803e224e6cab7a69 |

| 1247 | xfce4-session | /usr/bin/xfce4-session | 0c24d548599567fd6e6395bc24e80949cddb31967d57c2fea5f63bbcccd6055e |

| 1177 | lightdm | /usr/bin/lightdm | 2ee123681189b1630549d603be51c650e4d3341116e61a04907b25549c89d888 |

| 1000 | lightdm | /usr/bin/lightdm | 2ee123681189b1630549d603be51c650e4d3341116e61a04907b25549c89d888 |

| 1 | systemd | /usr/lib/systemd/systemd | 5cfc1481f6f476778e22b0edeb418ec8389a2caa5c034334a71f8b4246d8f974 |

+------+---------------+--------------------------+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Along with these examples, there’s also some complexity around caching process data that was retrieved and refreshing that data for a newer set. All of this will be considered as we build the UI.

Creating the ui Package

Throughout these examples, I’ll expose partial code for the sake of highlighting concepts. To see the full project, please visit https://github.com/arctir/proctor.

First, we’ll create a new ui package and setup a UI struct along with its

constructor.

type UI struct {

inspector plib.Inspector

// local refrence to process data, such that

// we don't always need to retrieve via the

// inspector

data Data

// when operations read or refresh process data

// use this lock to ensure the multi-threaded

// webserver does not mutate something being

// accessed

refreshLock sync.Mutex

}

// Data tracks process data and the last time it was

// retrieved from the system

type Data struct {

LastRefresh time.Time

PS plib.Processes

}

type DetailKV struct {

Field string

Value string

}

func New() *UI {

var err error

newInspector, err := plib.NewInspector()

newUI := UI{

inspector: newInspector,

data: Data{},

refreshLock: sync.Mutex{},

}

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return &newUI

}

It may be a bit challenging to grok all the things this code is doing without

looking into proctor, but bear with me — the key is the templated response

we’ll get to in a bit.

The main focus is the UI struct that will hold the state of our UI, underlying

data, and serve HTTP endpoints. A Run() method should be attached to UI,

which registers HTTP handlers (functions) and serves the endpoint.

const (

port = ":8080"

refreshPath = "/refresh"

processesPath = "/process/"

processesTreePath = "/tree/"

)

func (ui *UI) RunUI() {

http.HandleFunc("/", ui.handleAllProcesses)

http.HandleFunc(refreshPath, ui.handleRefresh)

http.HandleFunc(processesPath, ui.handleProcessDetails)

http.HandleFunc(processesTreePath, ui.handleProcessTree)

log.Printf("serving at %s", port)

panic(http.ListenAndServe(port, nil))

}

Each http.HandleFunc seen above will have a method that:

- Understands the request.

- Calls

plibfunctionality. - Uses results from

plibto parse HTML templates. - Sends the templated response and response code back to the client.

With this, we’ll end up with 4 types of requests:

/: Lists all process on a host./refresh: Reloads all process on a host; redirects to/./process/{PID}: Displays all known data about a specific process./tree/{PID}: Displays the hierarchy of a process.

To complete the handlers, we need to implement the 4 above:

// / Logic

func (ui *UI) handleAllProcesses(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ui.refreshLock.Lock()

defer ui.refreshLock.Unlock()

var err error

// retrieve process data from plib.Inspector.GetProcesses

ui.data.PS, err = ui.inspector.GetProcesses()

ui.data.LastRefresh = ui.inspector.GetLastLoadTime()

// create template and parse with plib.Processes

t, err := createTemplate(allProcessesView)

if err != nil {

writeFailure(w, err)

return

}

err = t.Execute(w, ui.data)

if err != nil {

writeFailure(w, err)

}

}

// /refresh Logic

func (ui *UI) handleRefresh(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ui.refreshLock.Lock()

defer ui.refreshLock.Unlock()

// clear process cache and recall /, which forces

// load of processes

err := ui.inspector.ClearProcessCache()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

log.Println("refreshed process cache")

http.Redirect(w, r, "/", http.StatusSeeOther)

}

// /process/{PID} Logic

func (ui *UI) handleProcessDetails(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

pid, err := getProcessFromPath(r, processesPath, ui)

if err != nil {

writeFailure(w, err)

return

}

// create template and render with plib.Process

t, err := createTemplate(viewProcessDetails)

if err != nil {

writeFailure(w, err)

return

}

err = t.Execute(w, ui.data.PS[pid])

if err != nil {

writeFailure(w, err)

return

}

}

// /tree/{PID} Logic

func (ui *UI) handleProcessTree(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

pid, err := getProcessFromPath(r, processesTreePath, ui)

if err != nil {

writeFailure(w, err)

return

}

hierarchy := getProcessHierarchy(ui.data.PS, pid)

t, err := createTemplate(viewTreeDetails)

if err != nil {

writeFailure(w, err)

return

}

err = t.Execute(w, hierarchy)

if err != nil {

writeFailure(w, err)

return

}

}

As you can see, the implementations for the handlers aren’t that involved. This

is thanks plib handling almost all the logic. In fact, the key here is to:

- Ensure we have a plib.Processes struct filed up.

- Pass it along with a base template to be rendered and returned to the caller.

- Use sync.Mutex to ensure that calls into the UI don’t mutate during a read.

In the above handlers, there are a few convenience functions that are called. Below you’ll find their implementation with some comments around the intent:

// getProcessHierarchy returns a list of processes starting with the most child

// and ending with the most parent. The most child will be the defined by the

// pid argument.

func getProcessHierarchy(processes plib.Processes, pid int) []plib.Process {

result := []plib.Process{}

currentProcess := *processes[pid]

for {

result = append(result, currentProcess)

if parentProcess, ok := processes[currentProcess.ParentProcess]; ok {

currentProcess = *parentProcess

} else {

break

}

}

return result

}

// createTemplate returns a final template with your template (temp) specified

// and wrapped with [UIHeader] and [UIFooter].

func createTemplate(temp string) (*template.Template, error) {

t, err := template.New("response").

Funcs(template.FuncMap{"pDeets": getProcessDetails}).

Parse(uiHeader + temp + uiFooter)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return t, nil

}

// writeFailure create a client response around a failed request.

func writeFailure(w http.ResponseWriter, err error) {

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusInternalServerError)

t, _ := createTemplate(errorView)

t.Execute(w, err.Error())

}

createTemplate provides a good transition to our next focus, rendering HTML.

This function takes the contents of variables uiHeader and uiFooter and puts

the temp argument (provided by the handler) in between them.

Templates

The ui variables described in the previous section are stored as const

variables in the source.

const uiHeader = `

<html>

<head>

<style>

.buttons {

margin-bottom: 1rem;

}

button {

background-color: black;

color: white;

border: 1px solid black;

padding: 8px;

font-size: 16px;

cursor: pointer;

}

table {

border-collapse: collapse;

width: 100%;

}

th, td {

border: 1px solid black;

padding: 8px;

text-align: left;

}

th {

background-color: black;

color: white;

}

.tree-wrapper {

padding-top: 10px;

}

.tree-list {

list-style: none;

padding: 0;

margin: 0;

}

.tree-list .tree-item {

position: relative;

display: block;

min-height: 2em;

line-height: 2em;

margin-bottom: 10px;

padding-left: 21px;

}

.tree-list .tree-item:before, .tree-list .tree-item:after {

content: "";

position: absolute;

display: block;

background-color: #333;

}

.tree-list .tree-item:before {

top: 0;

left: 10px;

width: 1px;

height: calc(100% + 10px);

}

.tree-list .tree-item:after {

top: 1em;

left: 10px;

width: 11px;

height: 1px;

}

.tree-list .tree-item:last-child {

margin-bottom: 0;

}

.tree-list .tree-item:last-child:before {

height: 1em;

}

.tree-list .tree-item:first-child:before {

top: -10px;

height: calc(100% + 20px);

}

.tree-list .tree-item > span {

display: inline-block;

padding: 0 5px;

border: 1px solid #333;

}

.tree-list .tree-item > .tree-list {

padding-top: 10px;

}

</style>

<title>Procotor display</title>

</head>

<body>

`

const uiFooter = `

</body>

</html>

`

const viewProcessDetails = `

<div class="container">

<div class="buttons">

<a href="/"><button>All Processes</button></a>

<a href="/tree/{{ .ID }}"><button>Process Hierarchy</button></a>

</div>

<table>

<tr>

<th>Field</th>

<th>Value</th>

</tr>

{{range $idx, $value := . | pDeets }}

<tr>

<td>{{ $value.Field }}</td>

<td>{{ $value.Value }}</td>

</tr>

{{ end }}

</table>

</div>

`

const viewTreeDetails = `

<div class="container">

<div class="buttons">

<a href="/"><button>All Processes</button></a>

</div>

<div class="tree-wrapper">

{{ range $value := . }}

<ul class="tree-list">

<li class="tree-item has-sub">

<span><a href="/process/{{ .ID }}">{{ .CommandName }} ({{ .ID }})</a></span>

{{ end }}

{{ range . }}

</ul>

</li>

{{ end }}

</div>

</div>

`

const allProcessesView = `

<div class="container">

<div class="status">

<p>Last Refreshed: {{ .LastRefresh }}</p>

</div>

<div class="buttons">

<a href="/refresh"><button>Refresh</button></a>

</div>

<table>

<tr>

<th>PID</th>

<th>Name</th>

<th>SHA</th>

</tr>

{{range $key, $value := .PS}}

<tr>

<td>{{$key}}</td>

<td><a href="process/{{$key}}">{{.CommandName}}</a></td>

<td>{{.BinarySHA}}</td>

</tr>

{{end}}

</table>

</div>

`

const errorView = `

<div class="container">

<div class="status">

<h1>Failed creating requested page.</h1>

<p>Error details {{ . }}</p>

</div>

</div>

`

At a high-level, uiHeader is holding the CSS and uiFooter the finishing HTML

elements. The expectation is that something like allProcessesView will be

passed in along with a supporting struct to render against. The {{ }} syntax

you’re seeing are Go templates, which can be read about

here.

While I won’t be digging into the features of Go templates today, let’s examine

the plumbing for viewProcessDetails. The end state rendered page looks like

this:

Taking a look at the {{range $idx, $value := . | pDeets }} inside of

viewProcessDetails, you’ll notice it’s looping to create the rows in the

table. The . represents the object that was passed in from the handler

function and pDeets is a mapping to a function we registered. If we look

inside ui.handleProcessDetails, you’ll see that it’s passing an instance of

plib.Process,

which is the root object, or .. The . | pDeets is templating syntax that

resolves as passing that plib.Process into the function mapped to pDeets. Go

templates have this weird model of registering functions to make them available

inside your templates. Inside createTemplate, you can see that

getProcessHierarchy is registered as pDeets. And that the argument it

expects is one of plib.Process!

If you’re new to Go templating this all might feel a bit foreign. As such, you may benefit by just templating out some simple HTML and seeing if you can make it work. As a final note, if you end up building something with a larger set of static assets, it may become impossible to keep them stored in variables as I have. In this case, you can look into Go’s embed package to point at external static assets that can be compiled into the binary.

Registering a ui Command

The final step is to add a ui command to the CLI such that proctor ui can

open a port for a UI to render on. How you introducing this subcommand depends

on how you’re rendering the CLI utility. In Go, most of us use

Cobra, and if you want to see how this is

wired up for proctor, visit the cmd

package. For the sake

of this post, here are the relevant functions for that package:

// SetupCLI creates CLI command structure

// call this from main

func SetupCLI() *cobra.Command {

proctorCmd.AddCommand(uiCmd)

proctorCmd.AddCommand(processCmd)

// more command here, ommited for brevity

return proctorCmd

}

var uiCmd = &cobra.Command{

Use: "ui",

Short: "Run the web-based UI",

Run: runUI,

}

// runUI defines the behavior of running:

// `proctor ui ...`

func runUI(cmd *cobra.Command, args []string) {

ui.New().RunUI()

}

The key takeaway in the above is that the plumbing leads to a call of runUI.

That then creates a New instance of the UI struct and triggers the RunUI()

logic.

Closing

In conclusion, embedding a UI into your CLI can greatly reduce the ramp-up time for users and provide an alternative way to interact with the tooling. By using languages like Go or Rust, we can easily produce frontends for our users. This certainly isn’t a model that will scale for non-trivial web interfaces or large scale web services, but it definitely scratches an itch in the CLI tooling space.